Michigan’s Energy Efficiency Can Lead to More Consumption, Not Less

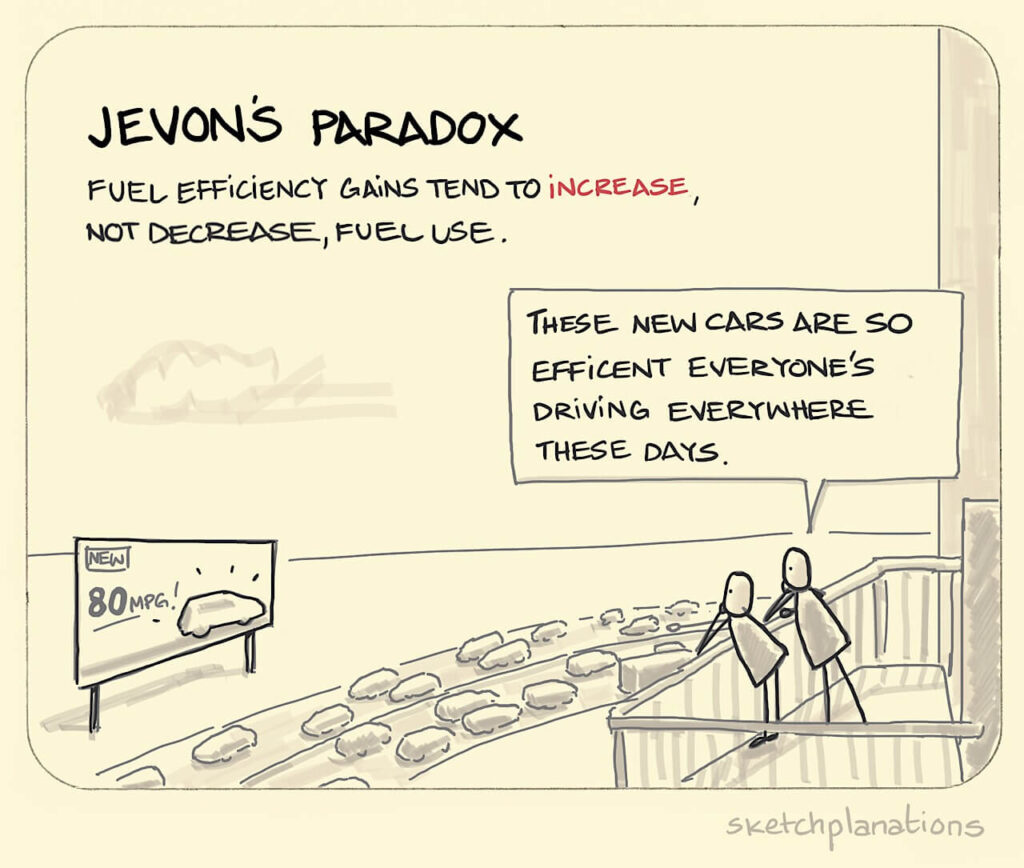

Increased energy efficiency creates higher rather than lower energy use.

Governments worldwide view energy efficiency as crucial for lowering greenhouse gas emissions. According to many decarbonization plans, increasing efficiency will account for roughly 40% of the emissions reductions required by the Paris Climate Accord (King, 2024). The rationale is straightforward: Using less energy should reduce overall consumption. However, history claims otherwise. British economist William Stanley Jevons first proposed the Jevons Paradox in 1865, which casts doubt on this belief. Increased energy efficiency creates higher rather than lower energy use.

Understanding the Jevons Paradox

During the Industrial Revolution, Jevons first noticed this pattern in coal consumption. He observed that coal use rose instead of falling as steam engines became more efficient. Why? Increased investment, economic growth, and ultimately higher total coal consumption resulted from improvements in energy efficiency that increased the profitability of coal-powered machines. In essence, innovations cause other innovations. (King, 2024).

This paradox has evolved far from its Industrial Revolution origins. Efficiency tends to boost energy use at the economy-wide level, even while it can lower energy use at the individual level. Successful businesses make more money, contributing to growth, new technology, and increased production. Different industries are witnessing this trend today, including those involved in hydraulic fracturing, also known as oil fracking, and AI-driven data centers, which have increasing electricity plans (King, 2024; Northeastern University, 2025).

The Rebound Effect: A Critical Consideration

Critics of the Jevons Paradox argue that efficiency improvements do not induce people to increase their energy use drastically. For instance, just because a car is 50% more fuel-efficient doesn’t mean a driver will travel 50% farther. On a larger scale, however, firms and sectors respond somewhat differently. Therefore, this is not an issue at the household level. Research demonstrates that consumers use more than half of the energy savings from expected efficiency improvements through increased consumption, a phenomenon known as the “rebound effect.” (King, 2024).

Industries with significant efficiency gains can cost-effectively extract and use energy resources that were previously too expensive. For instance, technological advancements that reduced production costs allowed hydraulic fracturing, or “fracking,” to spread (King, 2024). Similarly, AI and data centers benefit from more efficient computing power, yet their innovations drive energy demand up. (Northeastern University, 2025).

Efficiency Alone Won’t Solve Climate Change

The problem arises when politicians believe energy efficiency is the only way to reduce emissions. Research shows that it typically takes six years for improvements in energy efficiency to translate into higher overall consumption (King, 2024). Emissions will continue rising without additional policies that direct efficiency increases toward sustainable results.

What should politicians do? Investing in energy efficiency without limiting emissions or resource usage makes sense if the objective is to kickstart the economy. However, efficiency must be combined with a well-thought-out policy to balance sustainability and growth. For efficiency improvements to reduce long-term emissions, carbon prices, emissions penalties, and direct investment in low-carbon energy is necessary (King, 2024).

Moving Forward with Smarter Climate Policies

Jevons’ observations from more than 150 years ago are still seen today. Although energy efficiency helps increase access to services and enhance well-being, it is not an end-all solution for lowering emissions. Policymakers must recognize and address the rebound effect to develop successful energy policies. If they fail to do so, they risk being “surprised” when efficiency-driven gains ultimately lead to more emissions rather than less (King, 2024).

The Jevons paradox reminds us that even well-meaning environmental policy might have unexpected consequences as the world economy changes. Instead of allowing energy efficiency and concerns about carbon emissions to cause increased consumption, we can utilize these concerns as information for a sustainable future by developing plans considering this paradox (Northeastern University, 2025).

References/Graphics

King, C. (2024). The Economic Superorganism: Beyond the Competing Narratives on Energy, Policy, and Growth. Dow Jones Journal Report on Alternate Energy, November 11, 2024.

Northeastern University. (2025, February 7). Jevons paradox, AI, and the future of energy consumption. Retrieved from [https://news.northeastern.edu/2025/02/07/jevons-paradox-ai-future/]

Artwork: Jono Hey / Sketchplanations: Click Here